Emerging dangers – Investors’ Chronicle

15 min read- Old assumptions about globalisation and emerging markets are stale

- We live in a new age of great power competition between the US and China

- Environmental risk a key factor for emerging market returns

Two iconic images from summer 1989 were important precursors to the next three decades. Firstly, tearing down the Berlin Wall ended the Cold War in Europe and set the continent on a fast track to integration. Equally striking, Chinese students bravely facing down tanks in Tiananmen Square seemed like an auspice for democracy.

As it turned out, Europe’s project of ever closer union hit the skids and the communist party’s grip in China remains vice-like. The flame-billowing Chinese dragon is the undisputed winner from globalisation. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) now rates China the world’s largest economy on a purchasing power parity basis, estimating it is worth over a sixth more than the US’s.

Domestically, bringing tech billionaires like Alibaba (HK:9988) co-founder Jack Ma to heel shows the Party is calling the shots on modernisation. Sadly, the treatment of pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong shows dissent is scarcely easier than it was 30 years ago.

On the world stage, President Xi Jinping’s vision to transform China into the foremost power is firmly on track. Using its rapid technological advances and foreign-exchange reserves from years of trade surpluses to build influence around the world, in some ways China defies description as an emerging nation.

Certainly, there is further to go in bringing the nation out of poverty, but lumping China in with other countries is symptomatic of the blasé attitude by champions of globalism that compromised the west in the 1990s and 2000s. Their folly was to dismiss downside risks, rationalising that cheap imported goods meant low inflation for consumers and offshoring production would free up their own productive capacity.

The first assumption was right but the second led to slack in many western economies that they’ve struggled putting to use, hence the stagnation. The lesson is there are nuances in how mega-trends play out which can compound over time and become chasms.

Re-evaluating the old emerging markets narrative

The accepted investment case for emerging markets has been simple, centred on favourable demographics, comparative advantage in the cost of labour and an expanding middle class as nations get richer. Although these factors are fully evident in the growth and development of China and India, for western investors getting exposure to the best parts of their economies was always challenging.

Other countries, such as Brazil and Russia (which complete the now largely defunct BRIC acronym), were getting wealthier exporting energy, minerals and produce to feed the boom. Yet the great decoupling from the already developed world, especially the US and the mighty dollar as the global reserve currency, never happened.

In reality, the world has always been deeply connected and emerging economies are still heavily affected by policy decisions in Washington and Brussels. The relationship cuts both ways, the up-and-comers have likewise made a serious impact on western investors’ returns, although not necessarily in the ways expected.

The operational performance of listed companies in the US, Europe and Japan is directly affected by their supply chains in emerging countries and increasingly by sales to consumers there. What’s more, companies from China and other advancing nations already provide world class competition in new and established markets.

For portfolio managers, the relationship between shifting geopolitical and economic trends have been a factor in their asset allocation. Central banks’ loose monetary policy has been in response to crises in capital markets, but it has also been driven by disinflationary pressures caused in no small part by globalisation. This has kept bond prices high and is another factor in the expensive valuation of shares.

Inflationary dynamics change, and the prospect of rising demand for resources around the world could be another factor that sends inflation higher, especially as the world’s most populous countries start becoming net consumers of goods. A reversal of trends that have persisted for 30 years has the potential to cause mayhem in bond and currency markets.

What does it mean to ‘buy’ emerging markets?

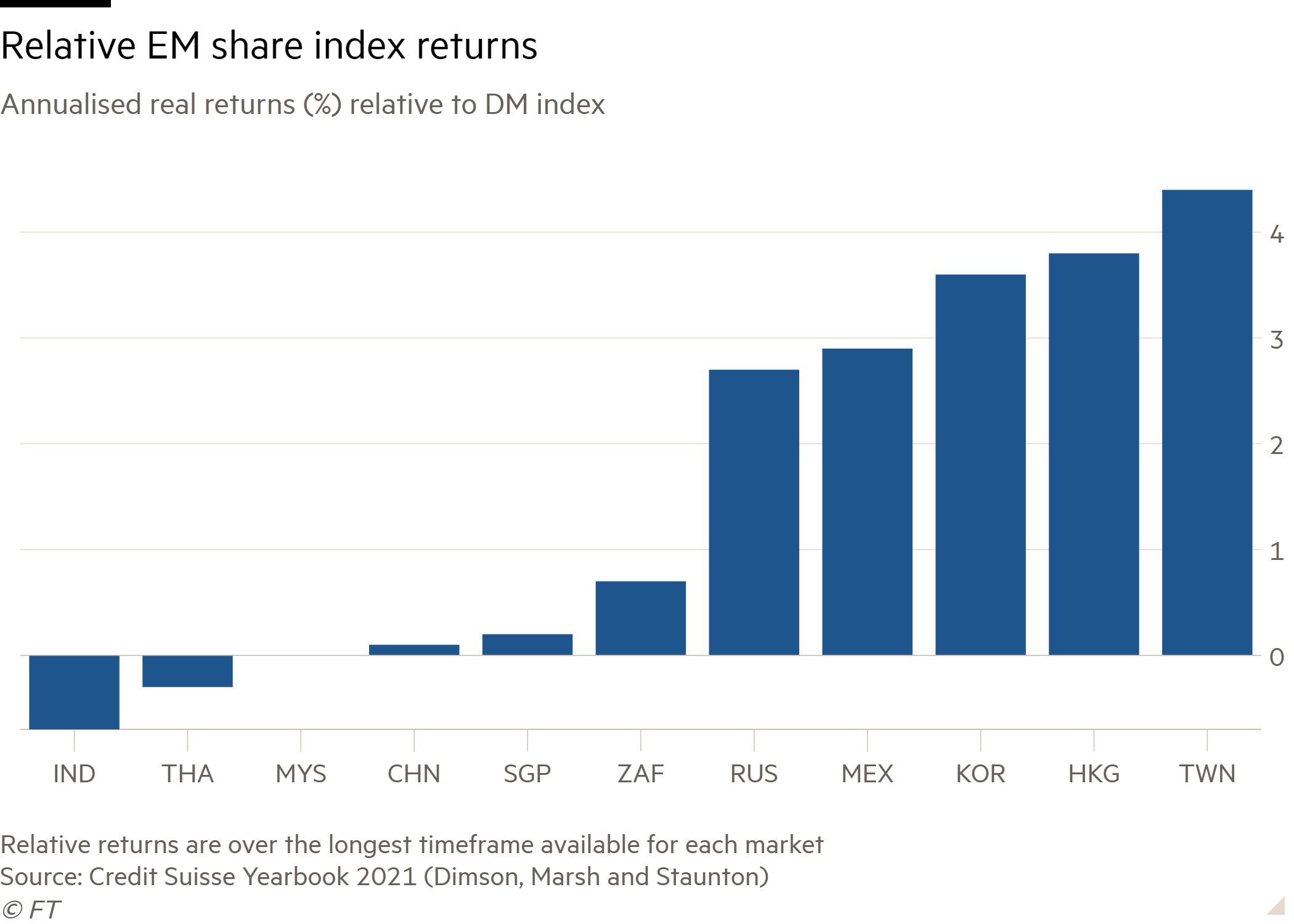

Growth rates in the developing world have clearly outstripped those in post-industrial economies, but there hasn’t been such a differential in the performance of stock markets. Emerging stock markets have done relatively well since 1990, but US-listed companies were the dominant driver of global returns, a trend that was marked in the 2010s as US tech stocks consistently beat earnings forecasts, making them irresistible to investors in a low interest rate world.

China’s representation in emerging market stock indices has been incomplete, which in part accounts for the aggregate MSCI EM benchmarks lagging the US equivalent. The evolution of capital markets in Shanghai and Shenzhen has opened the door to the inclusion Chinese companies warrant and now half of emerging market indices have exposure to China.

That dilutes exciting growth stories in other countries, adding to the case for active fund management. However, it must be said, the old growth model of low skill jobs moving to emerging nations cannot be taken for granted. As technology and services become more important worldwide, the level of education and skills within countries is increasingly important.

For example, although the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) is often said to offer tantalising prospects, many countries in the region lag behind in research and development spending. Furthermore, these countries rank badly in terms of the ease with which businesses can start. China has improved on both counts, which may stifle the ASEAN tiger cubs.

Unrest in Myanmar, Thailand and Indonesia also attests to political risk, and local knowledge is important. Discerning between the brutal crackdowns in Yangon and the umpteenth velvet coup in Bangkok, is partly where a manager earns their salt. Fishing for opportunities across the region, which also includes Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Cambodia, Brunei, and Laos, is more a case of checking well-laid lines than casting a net.

Expert stock selection is important, but in terms of the macro backdrop these countries will benefit from the competition for influence between the US and China. Inflows of capital will improve infrastructure, stimulate industry and productivity, and be good for the profits of listed companies.

Asset classes other than shares also offer value and a risk-to-return profile that has tempted western institutional investors. Bonds issued by ASEAN governments and corporations have become more popular holdings in fixed income portfolios. The term debt securities offer a higher yield than western counterparts, with the growth in the region making investors more relaxed about default risk.

ASEAN bonds are issued in local currencies and hard currencies such as the euro and the US dollar, with appetite increasing for both. Dollar funding has been a sensitive issue in the region since the 1998 Asian financial crisis and it provides another interesting sub-plot.

Back at the end of the 1990s, the US Federal Reserve’s decision to turn the screw on rates raised the cost of rolling over borrowing for Asian debtors. Today loose monetary policy by the Fed and its signalling of a continued dovish view on interest rates, has been seen as bullish for the South East Asian region.

That keeps the cost of capital down worldwide, and as more investors buy in the spread between ASEAN and US government debt yields will compress, making borrowing cheaper still. This illustrates the close relationship between international financial assets and therefore the risks.

Currency will be a key battle ground in the Sino-American rivalry and this will affect the region, too. In the 2000s, controversy centred on China keeping its currency, the renminbi, artificially low against the dollar to boost its exports to the United States. Now, the renminbi is becoming established as a reserve currency in its own right.

With China leading the world in development of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), the roll-out alongside Chinese payments and mobile communications technologies will only add to its economic clout. More inter-regional trade will also boost demand for renminbi, which means it’s an asset class that investors should consider.

Chinese government bonds are a way that institutional investors have been getting exposure and there have been noises about unhedged exchange traded funds (ETFs) being launched, although whether they’d be available on retail investor platforms is open to conjecture. The pure investment case is attractive, however: debt issued by a solvent government that runs the world’s largest economy and pays a yield far in excess of the US, Germany, the UK, Switzerland, or Japan.

Trump’s Asian blunder

Former US President, Donald Trump, was right to be concerned about the power of the Chinese government, but some of his actions in the Asia-Pacific region were strategic misfires. Shutting down discussion on the Trans-Pacific Partnership played into China’s hands.

The TPP would have been counterweight to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement, which was being negotiated concurrently. Signed in November 2020, RCEP is now the world’s largest free trade agreement. It covers 2.2bn people and comprises China, the ASEAN nations, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand.

Encouraging trade between developed and rapidly emerging economies in the region, RCEP demonstrates why notions of what’s EM and DM investing are becoming stale. Successful portfolio management will entail understanding the interconnectedness of economies and positioning for the best opportunities.

Liberal democracies such as Australia, with its resource-rich economy, are highly sensitive to demand from China. As we have seen when Australia raised concerns about treatment of Hong Kong protesters and Uyghur Muslims this year, China is quite prepared to hurt its critics in the pocket. Increasingly, ‘China risk’ is a consideration for many countries around the world.

India was a notable absentee from RCEP and, although the door remains ajar, some of its reticence is down to mistrust of its neighbour. In the 1950s, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru saw his newly independent nation and China as potentially the two pillars of Asia. The relationship has more often been one of tension, and scuffles between border patrols in 2019, although brawls rather than military engagements, hinted at the threat of serious incidents.

Countries with such huge populations are inevitably going to be rivals for resources. There will also be a tetchy balancing act as trading partners, deciding who has the comparative advantage in labour and upcoming technologies. India sees some protectionism as wise, and that is understandable given the way China has sought to achieve leverage over other nations through its role in their supply chains and essential infrastructure.

ESG risk and domestic strife weighs on India

The poor state of infrastructure drags on India and there is also massive dissent towards agricultural reforms. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government argues that consolidation and unleashing market forces will remove impediments to the agrarian revolution which textbooks tell us is a cornerstone of economic modernisation.

For downtrodden farmers the individual cost has been unbearable in many cases. Rather than starve quietly, they have determined their deaths should be an act of spectacular protest by the horror of self-immolation.

The social cost of what is deemed progress can be ghastly, but the environmental impact is potentially catastrophic. India still plans to rely on coal for much of its energy needs in the medium term, which has dire consequences for the planet and particularly for the sub-continent. India and Pakistan may be two of the least proactive countries in addressing climate change, but they are among the most vulnerable to its effects.

Water scarcity and the quality of sanitation and irrigation has always been an issue, but global heating raises the prospect of more frequent and devastating droughts. Aside from the ecological and human cost, the economic impact will be stark; the McKinsey Global Institute assesses a $200bn risk to Indian GDP growth by 2030 on current climate change projections.

Reflexive nature of environmental risk can put the brakes on growth

The externalities of environmental damage will present a greater obstacle to countries’ development, with the impact of climate change on food, water, and health set to cost governments and companies trillions of dollars. Populations around the world are at a critical size and the demand for resources is so rapacious that human development is rushing towards a Malthusian bottleneck.

Yet much of the infrastructure needed by developing nations requires a massive carbon credit to get them up and running. Cement, for example, is literally the binding glue for many projects, but is one of the worst sources of emissions. “If we rank cement with the world’s largest economies, it ties with India as the fourth-largest carbon dioxide emitter after China, the US and the EU,” says Andrew Ness, portfolio manager at Templeton Emerging Markets Investment Trust (TEMIT).

“China poured more concrete between 2011 and 2013 (6.6bn metric tonnes) than the US poured during all the 20th century (4.5bn metric tonnes)”, Ness highlights, and surges in demand will be necessary elsewhere in the world to drag people out of poverty and even build the renewable energy structures needed going forward.

President Joe Biden’s decision to return the US to the Paris Climate Agreement is welcome, but some of the criticisms his predecessor made were valid. The efforts being asked of the US to help limit climate change to one-and-a-half to two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels are not matched by those asked of India and China.

Tackling the climate crisis will be highly political and there is a worry that some regional blocs may underemphasise important actions the whole world needs them to take in their own jurisdictions.

Consensus on protecting the world’s oceans is even more elusive than for fair emissions targets, which is extremely worrisome as marine habitats support algae that suck carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and are the world’s most important natural sequestration asset. Trade agreements such as RCEP are more likely to exacerbate than alleviate the problem of over-fishing, an issue that surpasses even plastic as the greatest threat to these eco-systems.

Battling for influence and materials

If all nations don’t develop sustainably, there will be more losers than winners as damage being wrought now restricts the supply of resources in the future.

Vaccine roll-outs in the fight against Covid-19 demonstrate how emerging economies can be left floundering in a crisis and on the wrong end of a supply squeeze. Having natural resources is one thing, but developing nations have found themselves at the back of the queue for safe and tested vaccines.

Countries such as Russia and China have seized upon the opportunity to export their own Covid-19 jabs. What must be remembered is China, the world’s oldest civilisation, and Russia, a great power for centuries before the American constitution was born, do not consider themselves emerging nations. Their attitude to other younger countries is, like something from the board game Risk, played against America’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and counterpart organisations of its NATO allies.

Brazil is a case in point, it leapt at the chance to manufacture Russia’s Sputnik jab and it has gladly accepted CoronaVac from China. Hampered by the need to appease voters, western democracies have prioritised their own citizens. Vaccine diplomacy is helping the authoritarian regimes steal a march. Before Covid-19 Brazil was among nations seriously considering the place of Chinese telecommunications firm Huawei in its infrastructure; now Brasilia has closer ties to Beijing.

Leaders such as Brazil’s President Bolsonaro seem to offer allegiance to the highest bidder and whichever major powers chastise them least. The Trump administration proffered no condemnation over the reckless deforestation in the Amazon, so the west cannot claim moral superiority. What’s clear is that Brazil is part of the great game.

From the mid-19th century, the US has adhered to the Monroe Doctrine, a foreign policy credo that determined to keep all other powers off its patch in the New World. In the 20th century, the Cuban Missile Crisis and President Reagan’s farce in Nicaragua stand out in the long history of destructive interference by the US below the Tropic of Cancer.

Challenging American influence in its own backyard is a sign of equivalence to the US presence in South-East Asia. These geopolitical intricacies often override concerns about the environment and sustainability of developing countries.

For investors, active management is the way to seek attractive opportunities in Latin America. Being a major supplier of resources, western listed mining stocks with assets in the region are already a source of exposure. Other sectors will emerge; Brazil has a burgeoning fintech sector, for example, but the momentum of South American economies still centre on resource prices, the value of their currencies compared to the US dollar (which, as in Asia, affects companies’ borrowing costs) and inflows of foreign investment generally.

The new scramble for Africa

China’s financial muscle has been particularly evident in Africa, where its bankrolling of infrastructure projects has given it a firm footing. As of 2021 the China Africa Research Initiative, in association with the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, records that China has committed $153bn across 1,141 loans to Africa. The new military base in Djibouti is further physical evidence of global power projection.

Companies play a role, too. In Africa, internet connectivity has gone straight to mobile phones and WiFi, skipping the need for cable infrastructure. Huawei and its 5G technology will play a huge role and other Chinese companies are embedded in Africa’s development. Mobile banking, payments, messaging, and e-commerce solutions are areas of huge potential growth and businesses such as Tencent (HK:0700) and Ant Group can lead the way.

Ominously, the rapid development of the e-renminbi, China’s world-leading foray into CBDCs, could help it embed its currency in the digital payment infrastructure of emerging economies. With its companies as the soft emissaries it’s a real possibility that rapid adoption of their technologies could support China’s e-renminbi, making a very strong challenge to the US dollar’s global reserve status.

Rolling out digital currency combines with the leverage the Chinese government has on African governments through loans. Becoming a reserve currency in decentralised finance (DeFi), the blockchain-enabled monetary revolution that is expected to gather pace over the next five years, will help the renminbi knock the dollar off its perch.

Belt and Road leads back to Europe as China shoots for the stars

China’s policy of engaging with Africa has helped secure access to natural resources and it has done the same across Eurasia with its controversial Belt and Road initiative. Based on the medieval silk roads trading routes, being a major player in the supply chain and transportation routes will enable China to ensure its access to goods and services if there are global shortages, something that could happen due to high demand or productivity and therefore supply falling due to damaging factors such as climate change.

The recent announcement of a co-operation agreement with Iran was a powerful statement of economic diplomacy. Simultaneously the mullahs could defy the US – which by imposing sanctions has crippled Iran’s economy – and China can flex its muscles. Loosening the dollar’s grip on global commerce is the next step.

Closer trade ties with Europe are also controversial, and only serve to underline that China can’t be viewed by investors as an emerging market. Its capital markets are emerging, but as an economy and a power it is already racing towards pre-eminence. Becoming more influential in Europe and even setting the renminbi on the path to global reserve status aren’t the final frontiers; China is scheduled to begin work on its first space station imminently.

You can’t divorce geopolitics from economics and investing

An assertive China, combined with the global consequences of environmental policy in developing countries, means they are already big factors for future investment returns, regardless of direct holdings. In the past, emerging market equities were a way of diversifying returns from developed markets. These benefits still exist, but positive correlations between equity markets have risen.

It may be that going forward, the best diversification is offered by spreading non-western exposure into other asset classes, such as currencies and government bonds. Then there are commodities, which will still be volatile in recessions, but do hedge against inflation in boom cycles.

For investors in shares, the case for non-western companies is the cheaper valuation and potentially higher rates of growth. Different governance structures do pose a risk, as does regulation, although there are aspects of control that the west can learn from China, which is intolerant of its tech companies having too much power and abusing their market position. That may bring uncertainty for investors, but it encourages competition, which is healthy for the economy and capital markets in the long run.

There is also an argument that the demise of western dominance is a good thing. Africans do not even have to go as far back as the trans-Atlantic slave trade or Belgium’s brutal rule of the Congo to recount instances where they’ve been hard done by. Conditions of loans in the post-imperial era have in many instances been less benign than those from the Chinese.

Moral equivalence aside, China winning the upper hand completely would not be a happy outcome. The challenge for governments of other developed countries is to come up with a policy mix that acknowledges China’s power and engages it, without being hoodwinked. A core element will be sustainability in developing economies, that presents costs but where there is a need and competition for capital there are investing opportunities.